[ad_1]

What if Advent were less about which songs to sing which weeks and more about using our resources to ensure that all people are housed?

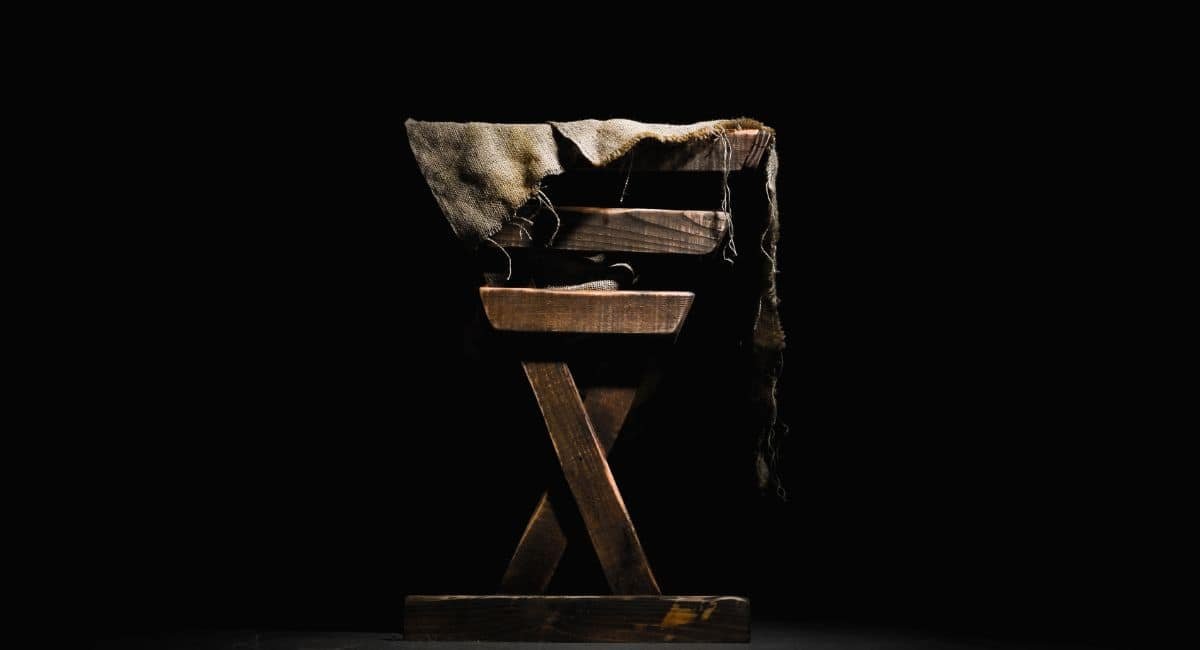

In the dominant theological imagination, including popular songs like “Away in a Manger,” Advent has been divorced from the grim reality of Jesus’ birth and the demands that this reality makes upon us today. Jesus comes from a colonized people. He and his family were refugees fleeing a repressive government at the time of his birth. The makeshift shelter in which the holy family settled and the manger which held the Christ child represent toxic charity and substandard housing. Even as an adult, scripture reminds us that Jesus did not have a stable home.

Why Away With The Mangers Began

In 2021, I was part of organizing the Away With The Mangers campaign (AWTM) with the faith community I was leading at the time, Good Neighbor Movement. AWTM mobilized faith leaders and neighbors around a conviction to do away with the mangers of our society such as bottle-necked rental assistance programs, slumlords, and decrepit housing. We organized to do away with the mangers of developers that displace low-income residents, American imperialism that displaces foreign neighbors, and toxic charity by churches resettling the same foreign neighbors that have been displaced by our country, the United States of America.

Our Work to #KeepJesusHoused

Jesus said that how we treat the least of these is how we treat him. The campaign called on people of faith and all people of conscience to amplify the message #KeepJesusHoused in advocacy for housing justice and safety for all people. At a local level, in Greensboro, North Carolina where Good Neighbor Movement is rooted, AWTM specifically raised awareness about the city council’s poorly administered rental and utility assistance program. AWTM also organized faith communities to fund a $10,000 #KeepJesusHoused mutual aid fund so that housing insecure neighbors could request direct cash assistance for urgent housing needs. Furthermore, Good Neighbor Movement produced the #KeepJesusHoused Liturgy for faith communities across the country to use in order to call for collective action to address housing insecurity in their local communities.

(Editor’s Note: This liturgy includes profane language in the week 1 content and week 4 song lyrics quoted as well as a reference to potentially triggering content in the prayer quoted in week 2. We encourage you to use your own discretion in viewing and using the liturgy. To access it, you can follow this link: #KeepJesusHoused Liturgy.)

Solidarity in a Virtual Teach-in

One of the most memorable moments of the campaign happened during a virtual teach-in. Cynthia, one of the neighbors facing housing insecurity that we met while canvassing, shared her story. Cynthia is a Black woman, mom of five sons, and had fallen on hard financial times during the pandemic. With her sons at home for virtual schooling, the utility bills had been higher than normal. Cynthia could not keep up with the rising costs to keep her family fed and sheltered. When she tried to apply for the City’s rental and utility assistance program, she was denied because she could not prove that her financial hardship was a loss of income caused by the pandemic. As she shared, I thought, In what world where resources are abundant and available should people have to prove their worthiness for what is theirs to have?

Cynthia began to cry. She shared that until one of our canvassers came to her door, she felt alone and despairing about her situation. The campaign gave her an opportunity to move from isolation to action and a sense that she deserved to be treated better by the city.

In that moment, a Zoom room became a space of refuge and care. The chat was flooded with messages like “it’s alright to cry here, sister,” “I am inspired by your courage,” and “that’s not right, you didn’t deserve that.” Then something happened that no one could have anticipated: Another Black woman unmuted and apologized for interrupting the program to say, “In my tradition, when someone gives a testimony, a Word, we call for a response from the congregation to give abundantly!” Cynthia accepted the offer, and after providing her CashApp, hundreds of dollars poured in from that makeshift community gathered over Zoom.

A portal had opened that evening for a group of strangers to be transformed, even if for a brief time, into a community of solidarity. What else do you do after the Spirit moves like this but open up in song! We unmuted, and with delays, sound feedback and all, we sang out, “Away With The Mangers,” the song we adapted from the original for the campaign to bring liturgy and direct action together:

Away with the mangers

No crib and no bread

Though houses are plenty

Kids caged n’ found dead

Some heat exhaustion

Some frozen to death

And Marcus Deon Smith

died gasping for breath

ARCO got off easy

Lynne Anderson gets a pass

Developers winning

City Council gets cash

Hiatt Street left scrambling

Refugees burned to death

Evictions skyrocket

While no ERAP is left

Away with the mangers

No crib and no bread

Church buildings are empty

Their soup kitchens crowded

They love to claim Jesus

But he was poor too

He’ll say depart from me Christians

Cause I don’t know you

He’ll say depart from me Christians

Cause I don’t know you

Away with the mangers

Choose to turn from your ways

Secure housing for all

Share the abundance of this place

Hiatt St came together

Refugees banded too

For those in power

The last word is not with you

For those not in power

True community waits for you.

A Note about the Song

We launched this campaign during several intersecting situations of housing injustice and moral contradiction. Refugees were being treated inhumanely by Immigration Customs Enforcement and the City of Greensboro (an apartment building owned by Arco Properties caught on fire due to failed code enforcement by the City, killing five refugee children, and later the City received a large settlement from Arco). A homeless black man, Marcus Smith, was having a mental health crisis during a downtown Greensboro event and died from being hogtied by the police rather than being provided mental health services. Latinx families in a Greensboro trailer park had the land on which their mobile homes sat rezoned by City Council and sold from under them by Lynne Anderson without their awareness, forcing them to relocate within a short period of time. All of this was happening while Greensboro’s eviction rate was the third highest in the country for cities its size and its rental and utility assistance program (ERAP) was not working fast enough to keep people housed because of the bureaucracy and hoops they made residents jump through to prove that they were poor and experiencing hardship. As a result, they discovered that they were out of funds while still processing hundreds of applications. Meanwhile, in the midst of this “housing crisis,” church buildings are largely left unused throughout the week except for “worship” on Sunday and their soup kitchens.

Using Liturgy to Speak to Injustice

The Away With The Mangers campaign is a model for faith leaders and congregations to reimagine how we use liturgy in the public square. It offered a way to bring the liturgy into direct encounter with pressing injustices in our local communities. It enabled people to speak truth to decision makers in order to make change. It also created an opportunity to invite others into the Jesus and Justice movements that we cultivate in our local communities.

Developing a Direct Action Campaign: How to Get Started

For churches that want to meet needs in their own communities through direct action, I recommend these five steps to discern how to get started:

1. Talk to people in your community and ask them what their biggest needs are

For us, Away With The Mangers started with knocking on doors and going to places where people in the community sought aid. We asked them to tell us about the biggest challenges they face and what change would most provide immediate relief.

Begin by going out and talking to the community. Ask people questions like: “What is one of the greatest needs you have in your life right now?” and “If one thing could be changed to make your life better, what would it be?”

2. Look for patterns in the needs that people name

When we talked to people, we heard them saying similar things. They were on the brink of eviction and struggling to pay rent and utilities. We noticed the pattern of needs around housing and developed the campaign to address that need.

As you listen to people in your community, ask yourself: Is there a pattern in these needs? Are people facing similar or connected challenges?

3. Consider possible systemic injustices in a widespread need

In our community, we knew that congregations often try to look for and provide resources to assist people in need. But we noticed that the people with whom we talked were having a lot of trouble accessing available resources. We realized that the housing needs revealed systemic injustice.

If you notice a pattern of need in your community, ask yourself: Does the widespread need reveal a systemic injustice that makes it harder for people to meet that need?

4. Bring the need and injustice to liturgy and scripture

Reflect on ways that liturgy and scripture might speak to the need and systemic injustice affecting people in your community. Ask yourself: What does the liturgy or scripture have to say about this need and injustice?

5. Partner with other people and groups

It is important to not try to do this alone. We were in consultation with peer allied congregations and activist groups that journeyed with us along this campaign to help shape the plan, debrief different activities we took, and improve along the way.

Reach out to people with more experience than you in organizing, and reach out to people and groups involved in the populations and communities with whom you are trying to connect. They can help you be more thoughtful about the mistakes you will make.

If you are interested in using liturgical direct action in your congregation and would like training, coaching, or consultation with how to implement this in your ministry, Brandon is available to support you through his consulting ministry, Wrencher Collaborative. You can contact Brandon by email to set up an exploratory conversation about your interest and vision.

Featured image is by Greyson Joralemon on Unsplash

[ad_2]

Source link

You must be logged in to post a comment.